Teaching Central America at an Atlanta Middle School

By Jonathan Peraza Campos

Every year, I pair my unit on story elements with Indigenous history and culture. I teach about the Maya peoples in my language arts class through the Maya K’iché creation story from the Popol Wuj. The majority of my Guatemalan students at my school come from Maya families, primarily the Maya Mam culture. It is my goal to help my students connect to their Indigeneity and their Maya heritage, especially as I see most of my students assimilating into mestizo Spanish-speaking Latino culture or monolingual English-speaking culture. Many of my students experience assimilation on both fronts, so I make it a point to show my students — Maya and non-Maya — how valuable Maya history and culture are through these stories.

Berta Caceres

This year, I taught the Maya creation story using the abridged version provided at the Smithsonian’s Living Maya Time website. I paired this creation story with the Muskogee Creek and Cherokee creation stories for our lessons on plot and story elements in my sixth grade language arts classroom. Students were tasked with determining the setting, characterization, conflict, and plot of the Maya creation stories and the Southeastern Indigenous creation story on whose lands we reside as Georgians. I used this unit focused on Indigenous peoples to also teach about Lenca leader Berta Cáceres and her peoples’ struggle for land and water sovereignty.

By the end of our study of Indigenous creation stories, I asked students which story was their favorite. Many of my students, especially my Maya students, shared that the Popol Wuj story was their favorite because it represented their heritage. In an open response quiz question, students said “It was about my people” or “my culture” or “I am Mayan like the people in the story,” which made it their favorite.

It became clear that teaching Mayan studies at my school is a crucial tool of culturally revitalizing teaching that we owe all of our Indigenous students and students of Indigenous descent. For that reason, Teaching Central America advisor and professor Dr. Emil Keme (Maya K’iche) and I are embarking on the Maya Voices Project alongside International Maya League and Escuelitas on Buford Highway to continue this work of reconnection and empowerment with metro-Atlanta Maya youth.

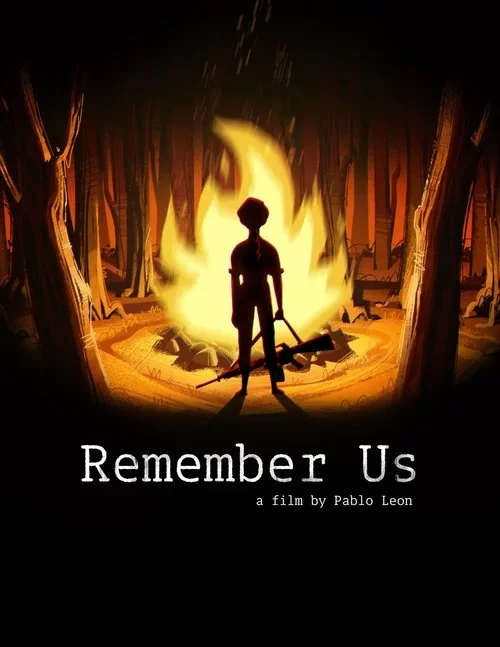

By the time we had concluded the study on Indigenous creation stories, Teach Central America Week came around the week of October 6. As a refresher of our standards on plot and elements of story but also to share an impactful film curated at Teaching Central America, I screened Remember Us directed by Pablo Leon, author of the graphic novel Silenced Voices. I asked students to determine the type of conflict and the theme presented in this film. Students accurately determined that the theme is just as the ending of the film states, “It's painful but necessary not to forget our history so our people don't get manipulated easily and repeat the same mistakes all over again. You may not believe your lives are important but your stories are. It's important to tell them, to keep them alive."

Using this film, I also shared my family’s history of surviving the Salvadoran civil war and of the people and childhoods lost in my family. I encourage my students to ask their Guatemalan and Salvadoran parents questions about their family history during the war eras so that we do not forget these critical moments of our past. We also made connections between the fascism of the 1980s to the re-emergence of fascism in the U.S. and El Salvador today.

Farabundo Marti

By Dia de los difuntos/Dia de los Muertos at the beginning of November, I found another opportunity to teach my students about Central American history and culture. In introducing Dia de los Muertos, I highlighted how the Guatemalan community of Sampango creates giant kites as a sacred tradition to welcome good spirits and ward off bad spirits. To our class altar, I added Salvadoran truth-tellers Oscar Romero, Rufina Amaya, and Farabundo Marti alongside my deceased Salvadoran and Guatemalan family members. Apart from developing an understanding of racism and imperialism, teaching students to connect to our ancestors is part of the work that I do as an ethnic studies and Central American studies teacher.

I am proud to be one of the few Latino and Central American teachers that my students have ever had in their schooling in Atlanta, though I hope more of us join the teaching profession. It is my mission to give my students the education that I wish I had received about my community. With great privilege, I teach my students about Central America while also supporting teachers and schools across the country with our resources at Teaching Central America.